TunnelVision

Decloaking Route-Based VPNs

CVE-2024-3661

Identified by Lizzie Moratti and Dani Cronce

Unmasking VPN Vulnerabilities

Virtual Private Networks (VPNs) are often touted as a shield against cyber threats, especially when connecting to untrusted networks like public Wi-Fi. However, recent revelations within the security industry have cast doubt on these claims. Over the years, researchers have uncovered small leaks in VPNs, primarily focusing on vulnerabilities in VPN servers. But what about the client-side traffic leaking on local networks?

Enter TunnelVision, a powerful technique that exposes VPN traffic even when users believe they are securely connected. Let’s delve into how TunnelVision works and its impact on VPN users.

How TunnelVision Works

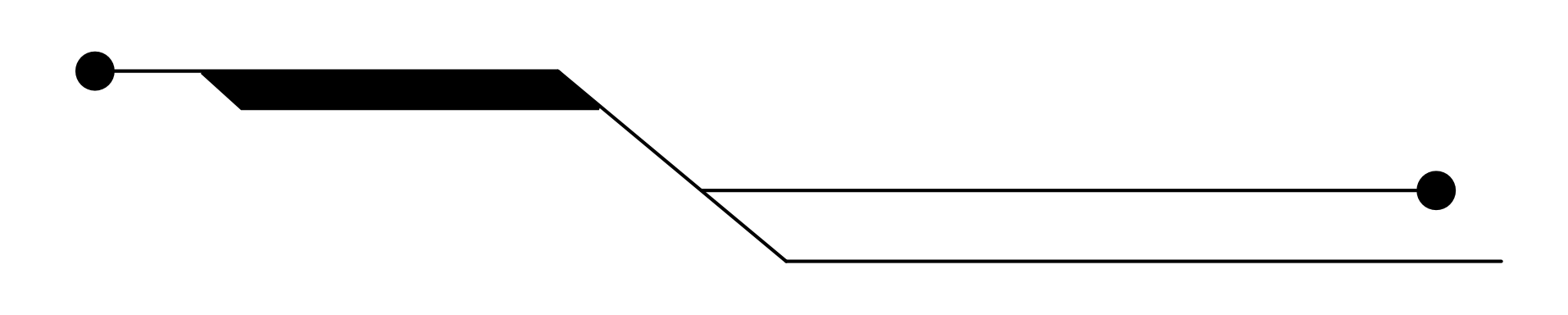

At its core, TunnelVision exploits the way computers handle multiple network connections. When you connect to a VPN, it becomes another network interface alongside your regular connections (like your home Wi-Fi or coffee shop network). These connections are governed by routing tables—rules that determine which network should handle your traffic.

Now imagine an attacker resides on the same local network as a VPN user. They are able to manipulate these routing rules, diverting traffic away from the VPN. This means that even though you appear connected to the VPN, your data may be flowing through other networks—completely bypassing the VPN’s protection.

In essence, TunnelVision achieves decloaking: revealing the traffic that should otherwise be protected.

Aftermath

The consequences are significant.

VPN users who rely on these services for protection on untrusted networks are just as vulnerable as if they weren’t using a VPN at all. TunnelVision undermines the very purpose of VPNs, leaving users exposed to potential attacks.

Stay informed and take precautions. Learn more about TunnelVision and protect your online privacy.

Frequently Asked Questions

How was this found?

We researched VPN threat models for a project and produced methods to attack VPNs. The team’s idea proved to be a severe issue, and we suspected it affected the entirety of the VPN industry. That’s when we began research in earnest.

Has this been exploited in the wild?

We have not seen evidence as of 5/6/2024 of exploitation in the wild. However, we believe this was possible as far back as 2002, so it’s possible someone besides us found TunnelVision but didn’t widely disclose or realize the severity.

In order to detect this, you would need to be reviewing DHCP network traffic and DHCP client logs. This might be possible retroactively.

Haven’t routing table leaks in VPNs been known for years?

Correct, routing table issues have been known for years. This is why the privacy and anonymity communities discourage VPNs. Most issues found have been small and patchable leaks.

How is this novel?

We have not seen any prior research using DHCP option 121 to inject routes and decloak VPNs, which is the novel part of our research. It also is not completely patchable in the same way smaller leaks have been (besides on Linux). We pointed to prior research on this topic related to routing table issues that have been known for years that we were able to find.

UPDATE: The purpose of this research was to test this technique against modern VPN providers to determine their vulnerability and to notify the wider public of this issue. This is why we agreed with CISA to file a CVE when we disclosed to them and why we decided to name the vulnerability.

After publication, we have received details about prior research into combining routing table behavior with option 121. These researchers showed that at least some people were aware of DHCP option 121’s effect on VPNs going back to at least 2015. Despite this, the research did not lead to wide deployment of mitigations nor the general public awareness of the decloaking behavior.

That said, we are grateful for the input of past researchers who explored the problem space. We will continue to credit our fellow security researchers who explored these issues.

Prior works referencing DHCP 121 route injection or VPN decloaking:

2017 Jomo’s Mastodon

2023 Lowend talk thread

Wouldn’t exploiting this be obvious?

Not really. The VPN user shows as being connected to the VPN. Attackers can control which IPs they wish to decloak, so theoretically they could choose to not decloak leak checking IPs. They could also leak DNS IPs while forwarding the traffic so the VPN connection is intact, but they obtain information about the traffic in the tunnel.

In no circumstances did we observe a VPN server disconnecting us with kill switches or other features.

Why are you saying the mitigation’s side-channel is so impactful?

When a mitigation is in place, an attacker can still obtain the destination you are talking to and the amount of traffic you are sending to that destination. Since most web traffic is encrypted with HTTPS, attackers can usually only determine the destination and protocol of the traffic anyway. This means the vulnerability that the mitigation introduces has nearly the same impact as decloaking.

The side-channel is also flexible in use:

The traffic can be checked against a predefined list of IP addresses.

The traffic can be selectively denied as a censorship mechanism.

The attacker can use IP space denial with binary search to determine all current connections in logarithmic time.

Why is this so bad compared to other leaks?

VPN providers often claim that no one, not even a network administrator, is able to remove your VPN protections. They may state it as “securing you on an untrusted network.”

TunnelVision shows that a network administrator can completely remove VPN protections. To make matters worse, we’ve demonstrated that an attacker who is on the same network has ways to control DHCP. This is demonstrated in our POC video.

Don’t most networks have widespread adoption of DHCP snooping or other protections?

Most enterprise networks do. However, most people using VPNs are not connecting from an enterprise network. They are connecting from public networks or their home networks.

In addition, part of the VPN provider threat model is they can secure any untrusted network, including those who do not have these protections.

Can you change the configuration of the DHCP server in the middle of a VPN session?

Yes. By setting a short DHCP lease length, an attacker can modify the configurations in the middle of a VPN session.

Isn’t most web traffic encrypted with HTTPS anyways?

This is true. If HTTPS traffic is decloaked it is still not possible to view the encrypted contents of the packet. For unencrypted protocols, the packet’s payload is readable.

However, it is still possible to see the destination and the protocol of the packet. Normally, that information would be inside the VPN protocol’s payload and encrypted.

Aren’t you going to be snooping on encrypted packets?

The packets will not be encrypted. DHCP option 121 will alter your routing table and send your traffic over a non-VPN interface, completely bypassing the encryption routine VPN application processes normally do. You can’t encrypt what you never receive.